| Sin-ying Ho |  |

Binary Codes: From Cobalt to Coca-Cola

by Michèle Vicat

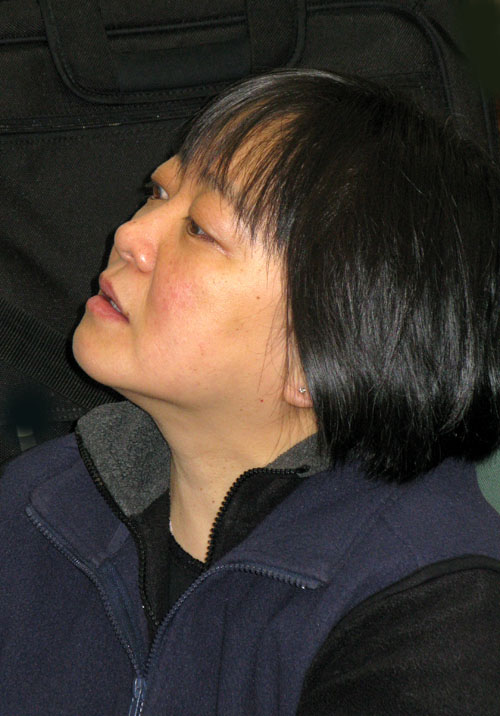

Sin-ying Ho photographed in her studio in New York by Michèle Vicat © 2011 |

Walking into Sin-ying Ho’s studio in Queens, New York, you might be intrigued to see three wooden boxes standing in the corner, each one taller than a man. The label on the side indicates that each box contains a precious and unusually tall object: a vase. Where did these vases come from and what are they intended for? To answer those questions is to embark on a journey that tells a story both of the passage of humanity through time and of the artist’s search for her personal traces.

|

The picture of Sin-ying Ho, perched on a stool in the shadow of her own creation, reveals a formidable determination to master technique and to go beyond ordinary craftsmanship and decoration to explore the creative process.

Lao Tse said, “A vase is made with clay, but it is its emptiness that fits it to its task.” With Sin-ying Ho, it is the emptiness that is propitious to the arrangement of stories. For her, material, shape and function are more than the properties that make an object. It is the presence of the vessel that underlines its form. Her work pushes the understanding of ceramics to new frontiers. For Sin-ying Ho, the crucial question as an artist is: “Do I want to paint on a vessel what I want to paint or do I want to paint something that I really want to know? Do I want to understand why this shape or form is so important for me?” Her first important encounter with ceramics was in 1996, when she was studying at Nova Scotia College of Art and Design and her teacher, the famous ceramicist, Walter Ostrom, sent her to study at the Jingdezhen Ceramics Institute in China. * It turned out to be more than a professional opportunity. The trip enabled her to create a link with the land of her parents and grandparents. Born and raised in Hong Kong, her story had already extended beyond Mainland China. Her father had left Guangzhou at age 18 because of the Cultural Revolution. From an early age, cultural and psychological confusion became Sin-ying Ho’s panacea. Raised in Cantonese at home, she studied Mandarin and English in a grammar school in a Hong Kong that was still dominated by the colonial British system. The family name was anglicized into Chinglish. Sin-ying Ho found it amusing when the apprentice came to her afterwards and asked why he had to learn the process since he had been doing ceramics from the age of six! “I explained, that it was a learning process to really understand the steps and not simply copy,” continued Sin-ying Ho. “I told him that he could eventually find his own touch.” It was a revealing moment for Sin-ying Ho. In China, students learn to copy. In Jingdezhen, Sin-ying Ho learned this assiduous and strict approach: “With this approach, I asked myself how and why Chinese art has such a longevity? It is a question of style defined at a certain point. It also has something to do with Confucianism. You should respect your teacher, you should learn from the teacher. When I was in Jingdezhen, my question was, ‘Why do we have to perpetuate techniques that were established in the 10th century during the Song Dynasty?’ I think it comes from the culture. It is the way Chinese culture was encouraged.” In that context, where is the place for an artist like Sin-ying Ho? Not only in China, but in the general environment of contemporary art? To be a ceramicist today means confronting social and artistic challenges. How is it possible to accept ceramics as a concept more than a function? Betty Goodman shattered the vision of ceramics in the 1950’s by treating ceramics as a symbol and elevating it to a sculptural level. Sin-ying Ho’s vision of ceramics explores her personal cross-cultural experiences. “As an artist,” she explains, “we can add a new line, but we also have to think about culture. It is a question of communication between you and people, between you and your work. You work to exhaustion, but you keep the connection with the world and with the culture. If I look at China today, it is not a question of change between tradition and contemporaneity. Why people are still so fond of Buddha while being so capitalist at the same time? It is something fundamental to Chinese culture and people have to work their way to newness through visual and intellectual thinking. When I go to China today, my philosophy is ‘Eat what they eat, see what they see, read what they read.’ Although China will transform into a new culture, that new culture is based on a strong ancient one. It took generations and generations to embed that and it will take generations and generations to embed the new culture. It will become a new form of a new culture.” Ceramics was not her first choice. Sin-ying Ho went to Canada to learn acting, and acting taught her that language was her best tool to deliver her story if she wanted to survive. Sin-ying Ho chose ceramics because of its association with language. She points out: “ If you take a dictionary, the definition of a language is a tool for communicating. It is thus man made; it is done with symbols. Chinese language is based on pictorial images. It uses symbols. It is like a drawing.” Sin-ying Ho realized that ceramic language was the key for her to go beyond her own culture. She found universality in the way humanity is recorded when symbols are fired in a kiln. If people do not understand the symbol per se, it may be perceived as decorative. But, it can also transcend the uniqueness of a specific meaning in a specific culture. It can draw fresh horizons for people bombarded with the new languages produced by the globalization of the world. Porcelain was her way to link ceramics with her personal archeology and the dispersed fragments of cultures she encountered or she studied. Ceramics gave her a new stability. She explains: “ When I learned ceramics, my teacher taught me the language linked to it. ‘This is the lip, the neck, the shoulder…’ It is all sensual and it goes back to humanity. Ceramics has a permanence through its nature and life.”

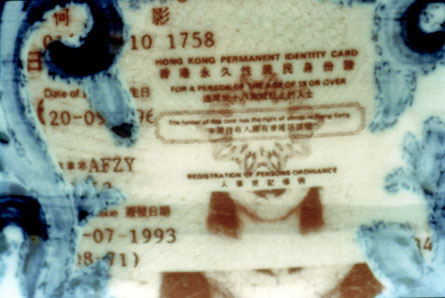

Identity reflects on the notion of acquired and perceived heritages. Hair and skin are metaphors that Sin-ying Ho likes to use. Their DNA won’t change. Even though her hair is black, she could decide to change its color, but its DNA would remain the same. The perception would be different, but the acquired heritage would be unchanged. Definition of nationality, family name, and identity are put to the test in her case. She has an English name (Cassandra) and an English-Chinese one (Sin-ying Ho) as well as various passports and travel visas (a Hong Kong Identification Card, a British and Overseas passport, a Chinese Travel Visa, a Canadian passport and an American Green Card). These are the ingredients that permit her to tell us that, although she is Chinese, she is living in a larger environment. She can cross the boundaries of her heritage while she is also able to delve into her cultural legacy. Still, it is far from tranquil.

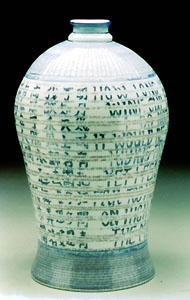

Her piece called Gibberish III, shows her fascination with languages and their structure. Classical Chinese language is written from top to bottom. English is written from left to right. What about letters and pictograms that are replaced with digital code? This was the beginning of her questioning of established codes of reference. Painting a lotus flower or a peony on a vase could lead us to a narrow interpretation if we only see them in a Chinese context. She wants to avoid categorizing elements according to a specific heritage. Sin-ying Ho does not confront symbols between East and West. She tries to facilitate our passage between permanence and impermanence. What a society retains from the past becomes its cultural trademark. The blue and white (qing hua) motifs on the Chinese porcelain belong to one thousand years of expertise. It is during the Ming dynasty that this type of porcelain arrived at its apogee because the Chinese people discovered cobalt on their own territory. Previously cobalt came from the Middle East. The blue and white motifs are also images that are associated with our vision of Chinese art.

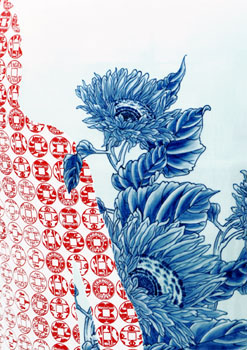

In Temptation: Life of Goods, No.1, Sin-ying Ho adopts floral motifs not only as a code of visual reference, but also as a way to connect conceptually with her identity. But, the “Asianness” of a blue and white peony is only one element that the West has kept from fruitful commercial exchanges. We do not remember that the peony represents prosperity and nobility, and that a peach symbolizes longevity. For us, it is all Chinese! Confronting the voluptuous texture of flowers with patterns that belong to our contemporary visual trademarks reveals how our stories dialogue with the past. Here, we have names of our global commodities. Starbucks, Coca-Cola and Piaget are immediately recognizable in Beijing, Berlin or Sao Paulo. These brands do not need a painstaking work of reproduction to take effect. Just the name and a crude logo are sufficient to define our belonging to the new world. Sin-ying Ho borrows the motifs from the computer. The decals are then transferred to the vessel.

In the series In a Dream of Hope, No.1, the artist shows digital numbers from the Shanghai Stock Market and from the Down Jones. They are the traces of our new cultural and global ways of communication that we are already passing on to future history. For the last few years, Sin-ying Ho has been developing the notion of series. “In the past, I was working on one form, one idea,” she says. “But, as an artist, you are not satisfied with this simple idea. I started to juxtapose different forms together and also to orient them differently. I then realized how many variations I could have. From these variations, I used the content to separate them into different series.” She acts like a stage director. One theme could be created and deconstructed as our world is constantly evolving.

The swollen and rounded shapes of Made in the Postmodern Era (series No. 4) make us glide along with the sails of our myths. Far from a linear exploration, the artist is now able to seduce us into a conversation under construction. Mao Zedong and the Chinese dragon rub shoulders with Mona Lisa, Andy Warhol and Marilyn Monroe. The vessel becomes a souvenir box in which we enclose history. The images may become the caricatured remnants of our selective memory. Things may lose their meaning. We can reenact them with another interpretation. This suppleness of expression challenges Sin-ying Ho to develop larger forms while respecting the essence of ceramics. Technical problems may arise such as the collapse of the neck of the ceramics during the firing process. The series Garden of Eden responds to her need to understand where things come from and how they continue to be with us. “If I look at what happened in 2008 with the economic crisis, I know that I have to look deeper into human traits,” explains Sin-ying Ho. “What makes me the same and different from others despite the economic crisis that the humanity is experiencing? What is my real nature? “ Eden is the metaphorical place where she can start to draw the symbols through which everybody could find love and peace. Flowers are part of a garden and Sin-ying Ho selects them from the Chinese vernacular. Poets and scholars use them to describe seasons and months. The Chinese garden was established, but also transformed over the last 3,000 years. Flowers mean that something new and different is happening. We should be able to accept the change.

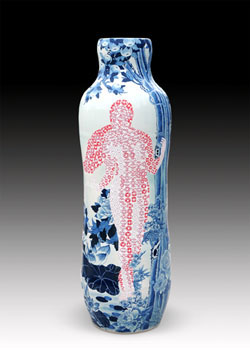

In Transformation: Motherboard No.1, Eve is holding the fruit of knowledge. She was the knowledge once, and the artist paints her figure full of computer chips. Eve belongs to our time; she becomes a trace of our digital era. We continue to survive through the same process as a formal garden: implementation, taming, transformation and grafting. The butterfly echoes our constant transformation. The importance and the ramifications of the story of the Garden of Eden are such that Sin-ying Ho felt that one vase was not enough. The story will never end. She needed to return to Jingdezhen to implement her ideas. Only there, could she find a kiln big enough to support her vision, to go a step further. The result is unique and astonishing: four vases ranging from 69 to 77 inches high. The story can be deciphered on one vase, but can also be read as a pair. “The two vases are slightly different, but play as a pair,” she says. “With my series Garden of Eden, I am pushing the limit, but I am also working with pairs…a reference to Adam and Eve. If the pair survives, we have two vases of the series that can reach the story of the other pair. But, if one vase were to break, the story could also continue and still be connected, because the vases were different to start with.” Physically, we are back to Sin-ying Ho’s studio in Queens, New York, where the wooden boxes finally reveal their secret. A garden is there, waiting for the blooming of the flowers. Sin-ying Ho’s narration is embedded and fired on the ceramics. She visually tells the story of mankind and its evolution from Stone Age through Digital Age. In terms of physical evolution, there are differences, but the notions of search and transformation are transcendental. * see our previous interview with the ceramicist Charlotte Nordin for explanations about Jingdezhen (section Currents.)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||