|

|

| Wang

Jianwei's Symptom at Nyon

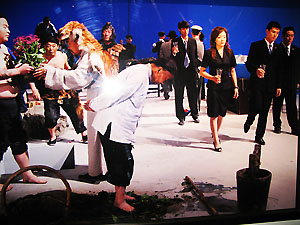

Zhang Ga explains that Symptom “offers a formal language on the surface. But, underneath, there are costumes, dramas, historical references and a unique vocabulary.” A symptom is what a patient feels when something goes wrong in his or her body or mind. It is what the patient tells the doctor. But the degree of information provided by the patient reveals his or her background and understanding of the chronological order of the development of the symptom. On the other hand, the reading given by the doctor comes from his or her scientific approach and experience. So, what is the exact relationship between a patient and a doctor? And what can solve the problem? What is the part of science, art and philosophy when it comes to sensing the vulnerability and the instability of a society? The patient is a metaphor for the society composed of individuals taken despite them in the farce that is History with a capital H.

Born

in 1958, Wang Jianwei started his career in the late 1970s

as a painter. From the beginning his work was engaged

with social interactions. New media, introduced in China

in the early 1990s,

gave him a flexible format that was just beginning to

be elaborated even in the West. New media gave him a vehicle

to think about

and to express the new paths that his country was suddenly

being allowed to take. A broad new avenue for history was

traced by

the officials. But for a population still stigmatized,

it was an avenue leading to the unknown. Artists like Wang

Jianwei

took small alleys emerging from the avenue swelled with

official messages promising an economic future, but giving

no key to create

new models for expression.

The

videos are treated as mini-historical frescoes in which ancient

China, the overthrow of the Imperial

China, the

early Republic,

the creation of the People’s Republic of China

in 1949, the open door policy in 1978, and the integration

of the country

into the global economy are compressed and mixed along

a single time line narrative. The artist, Wang Jianwei,

confronts us

with history in its purest stereotypical perception.

How does the West know China? Where are the nuances

between our romantic

vision of the past and our fears about a new imperialism?

Stereotypes activate our behaviors. Here they explore

how our knowledge is

constructed when historical, social and cultural elements

are interacting. Wang Jianwei says, “Stereotypes

work on the visible and the invisible; on the relations

between East and

West.” For this reason, characters that he stages

in his videos and photographs come from different times

and

social levels

although they are all Chinese. The superimposition

of historical contexts, social amalgam and individual

paths

make them

strangely identical and out of phase. This feeling

is enhanced by the

fact that the photographs look like prints taken from

the videos.

In fact, they are carefully, methodically constructed

as momentum of time. The effect is three-dimensional.

Incorporating

a banal object such as the armoire is enigmatic or even disturbing.

But is this not

a strong

relationship

to the characters staged in the videos and photographs?

They are

costumed and they act as individual anomalies though

they follow the artist’s scenario. The sounds and

the motion of the armoire strangely echo the methodical

behavior of the characters.

I asked Wang Jianwei how he conceived the relationship

between the armoire, the film, the videos and the photographs. “The

relationship is with the title of the exhibition,” he

told me. “Videos are directly taken from

performances. Photos are not taken from the videos.

This is another

work. We are

thus in the same situation but we do not find the

exact copy. The

armoire is to be understood in that sense when

things belong to the same situation but are also

independent

while being

linked. In Beijing, I did a sculpture from a photo

of the first bomb

that was built in China. I wanted to represent

the bomb the way it was. The bomb never exploded

in reality

but

it became

a very

strong political symbol. The symbol becomes a brand.

It is irrelevant whether the bomb explodes or not.

It is the

symbolism

that counts.

It is the same here with the armoire. We link here

with the title of the exhibition, Symptom. It is

like somebody

who

is sick and

goes to the doctor. This is not a simple question.

It is not a question of going to the doctor and

mentioning bodily

changes.

It is like a detonator. A detonator that indicates

a

change. It is the same in politics.”

|

All material copyright 2010 by 3 dots water

Zhang Ga, Curator of Symptom,

Zhang Ga, Curator of Symptom,  Vincent

Lieber, Conservateur du Château de Nyon,

Vincent

Lieber, Conservateur du Château de Nyon,