| LIN YAN |

Calligraphy

by Liu Yongqin © 2010

Calligraphy

by Liu Yongqin © 2010

|

"At the Frontier of Different Universes"

by Michèle Vicat

|

Portrait

of Lin Yan, photograph © Michèle Vicat, 2010 |

Lin

Yan remembers looking at art in the Centre George Pompidou

in Paris and liking it but being

unable to relate what she saw with the city around her. “I

could not find the intimate connection between the work exhibited

and the culture which the city valued,” she says. “I

understood that I had to come to America to connect with another

part of culture. I felt I had to come to New York to understand

contemporary art.”

Lin Yan, who was born in 1961, belongs to a generation of artists

that received a strict education in drawing and classical western

realist painting. Besides technique, she learned the perseverance

necessary to attain the level of perfection expected by her

teachers at the prestigious Central Academy of Fine Arts (CAFA)

in Beijing. She was educated in an atmosphere of intense competition.

Progress on the work itself was the rule. It was the requirement

to be noticed, to be considered the best. The system gave very

little individual freedom to the average student. But Lin Yan

did not come from an “average” environment. Her

parents and maternal grandparents had already established themselves

as respected painters in China. They provided her with the

necessary link to connect her education to a cosmopolitan world

and to endow her a sense of exploration and experimentation.

|

|

Her maternal

grandfather, Pang Xunqin (Hiunkin Pang), was trained in Paris

from 1925 to 1930, and her grandmother, Qui Ti (Schudy), studied

oil painting in China and Japan in 1928. They brought the colors

and techniques of Post-Impressionism and Fauvism back to China.

Pang Xunqin created the Storm Society, an avant-garde group

in Shanghai. Qiu Ti was one of China’s first female oil

painters. Pang Tao, Lin Yan’s mother, was a visiting

artist at CAFA’s studio in Paris and did research at

the Ecole des Beaux-Arts for a year, where she became the first

Chinese professor to depart from realism. Lin Yan’s father,

Lin Gang, studied western art in the Soviet Union. The family’s

involvement in modern art made it a target for radical political

movements in China. The fact that Lin Yan’s grandfather

had established China’s first school of modern art and

design resulted in his being labeled a “Rightist” for

more than twenty years. Lin Yan’s parents were sent to

the “5.7 Reform Camp” during the Cultural Revolution.

Lin Yan was left behind in Beijing, with a succession of different

families.

Lin

Yan, "Tree" series, Xuan paper and ink,

45" x 12" x 2.82", 2010 © Lin Yan

|

When she started her college education at CAFA in 1981, Lin

Yan quickly drew the line between what was expected from

her

as a student and what she could obtain as the daughter of her

rehabilitated parents who taught and lived on campus. She had

access to books only available to faculty members. The privilege

enabled her to look at things differently and to develop her

own opinions. She was fascinated by the way Kandinsky related

color and music together. It introduced her to abstraction.

But she also realized that she had to be careful; she needed

to give her teachers what they expected from her. At home,

she kept a personal sketchbook for her abstract work. Her parents

warned her that she would never find a job if she persisted

in her fascination exclusively with abstract art. But she had

already made her choice. The path towards abstraction would

provide a central spine for her own contradictions to dialogue

with each other rather than resulting in a collision.

Lin Yan graduated from CAFA in 1984 and taught in a middle

art school annexed to CAFA. She applied and was accepted to

several universities in the United States, but decided on the

spur of the moment to go to Paris. “My mother was in

Paris,” she explains. “She found a sponsor for

me and sent my portfolio to the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, which

accepted me. It was a turning point in my life. I was excited

to be away from home and to meet so many interesting people.

Although I loved Paris, I was still thinking about America.

I had come from China, a country with a long history. I was

now adjusting to life in another traditional culture. I felt

a bit overwhelmed in trying to find who I was. The sky in America

seemed higher to me.”

During the year spent at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, she studied

how to make and use artistic media and techniques. It was an

educational springboard, which expanded her options. This established

the foundation for her to explore the materials she was to

use in her art over the next twenty-five years. She later discovered

the multiple possibilities of paper, a medium unique in Chinese

art. She also learned that she could afford to be different.

She did not have to compete with other students to succeed.

She no longer expressed herself by simply reproducing a model.

Instead, she began to feel her work and through that to discover

what was inside her.

The sophistication of Paris spoke deeply to the young girl.

She could relate to the city’s old buildings as well

as its culture and history. Beijing and Paris have that in

common. A discovery was the light of the Ile de France. It

was the light painted by the Impressionists. She could finally

connect it to their paintings. Her relationship with the city

was romantic. When it came to contemporary art, Lin Yan found

it difficult to relate the works in the Centre George Pompidou

with what she saw around her. She could not see the intimate

connection between the work exhibited and the culture emanating

from the city. She would have to go to America to find that.

Her dream had always been to go to the United States and very

precisely to New York.

Lin

Yan, "Give Me a Title #C and #D," Series started in 2009,

© Lin Yan |

Before going

to Paris, she had pointed her finger close to New York on a map

and applied to different schools. The University

of Pennsylvania at Bloomsburg offered her a full scholarship.

On a map, it did not look that far away. When she arrived in

the United States, she took a bus, confident that it would

only be a short trip to Bloomsburg. After two hours, and still

not close to her destination, she said to herself “Whatever!” She

was in the country that would give her the potential to find

her own space. A space that connected her directly to contemporary

art without compromise.

As with many artists who live between two cultures, the process

of assimilation (or, at least, the understanding) of the new

environment involves an internal reexamination of one’s

home and its traditions. But when Lin Yan went back to Beijing

for the first time in 1994, she could barely relate her memories

to the reality that confronted her. Entire chunks of the old

neighborhoods were gone. The soul and the pace of Beijing had

been altered. “The old city was almost gone,” Lin

Yan says. “It was a mess of new high-rise buildings.

Through the dusty air, you could see everywhere that the old

landmarks were being demolished and replaced with poorly designed

new buildings. The philosophy was that only new things were

good. It’s really sad to watch. Old Beijing was well

designed as a whole. Although it was in a very bad condition

after all those turbulent years, you could still see that the

combination of landmarks was like a poem. The rhythm of the

city was like endless story telling. Now you can only find

few soulless, commercialized, isolated, repainted traditional

landmarks.”

|

|

Lin

Yan, "Qi #2-To My Hometown",

Oil on woodboard, with

chain & wood,

83" x 76" x 100", 1994, © Lin Yan |

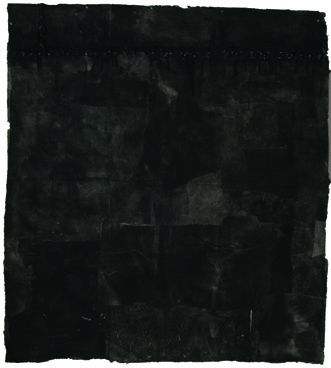

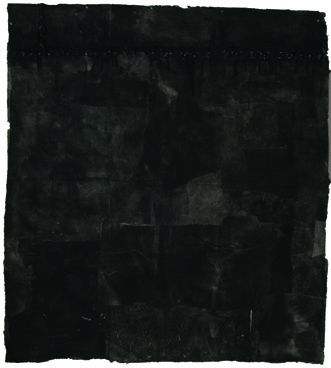

Her

first black series Qi is a reflection on deterioration. Qi

#2 -To My Hometown is at first very disturbing, nearly violent. The

work depicts the shock experienced by the artist. It is a primal

scream, expressing contradictory but inevitable forces. We are a

world apart from the stereotypes of what was old Beijing. But the

work is not a reference to the physical aspect of the city. It is

a quest. How do you go back to your roots? What fragments would you

put in the suitcase called memory? For Lin Yan’s generation

of artists, there was a Manichaean division of the world between

the communist society they came from and the capitalism they encountered

on their arrival in the United States. But that dichotomy was already

disintegrating when she returned home. Beijing was suddenly under

the yoke of an intransigent capitalism. The destruction of traditional

environments expressed how the Celestial Empire had finally reached

heaven! Lin Yan found the worst of a capitalist society. It was unexpected

to someone trying to re-connect with her own society and its values.

The cultural edifice was on its way towards annihilation.

From that point on, Lin Yan started a voyage that brought her deep

inside herself by consciously eliminating external distractions. Utopia

was gone. She had seen the materialistic transformation of what made

her youth. New materials, new heights, new volumes and new proportions

became the new core of her society. She needed to find a point of equilibrium

that would help her to resolve the tensions between her two worlds,

the East and the West; between the origins of her life - her memory

- and the adoption of her adult life - her history.

Her work became more and more “minimalist.” It took the

path of bringing stories together, a transaction by which she bridges

duality, conflict and contradictions.

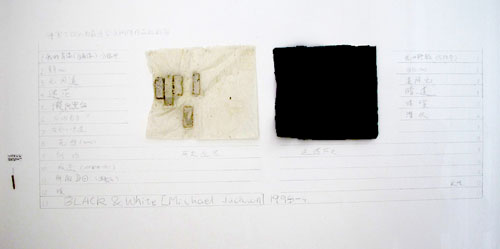

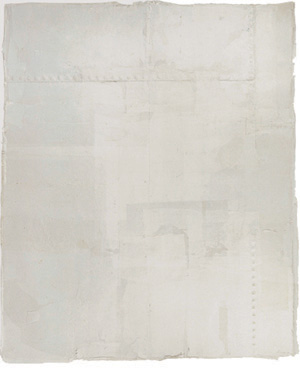

Her palette of black and white helps her to go to the essence of abstraction. “There

is nothing much to talk about” says Lin Yan in an interview given

to art curator Liu Libin in 2006. A definition like a scalpel: there

is no compromise. To discover the true nature of the world, one must

find oneself.

Lin Yan believes that, as an artist, she can take old patterns and

old techniques to create something new.

Black and white are the fundamental colors of classical Chinese art.

White is the natural color of paper. Black is the color of ink, the

vehicle that allows the transmission of ideas. Combined, paper and

ink are the memory, the DNA of Chinese culture. Grey/Black is also

the color of Beijing. The original houses in the “hutongs” (small

alleys) were built with grayish bricks and tiles. Black was considered

the “king” of colors in ancient China. It is associated

with water, one of the five elements that compose nature. Black equally

plays with white in the unity of Yin and Yang in the search for harmony.

To reach infinite variations in her black palette, Lin Yan mixes different

black oil colors with mat or gloss media to create subtle feelings.

She also uses acrylic, tempera or wax. “Black is not a unique

color. It has a complete palette. From Chinese paintings, I learned

how far I could go with only black. For ten years, I used different

blacks on different media. Since 2005, I have used only ink. I used

different Chinese paper as media too.” Quite naturally, Lin Yan

came to use handmade xuan paper and mulberry paper (xuan zhi and pi

zhi). Each kind includes a wide variety of paper made from the bark

of a type of elm tree or mulberry tree. Created during the Tang Dynasty

(7th century AD), it was used largely by painters and calligraphers.

Lin Yan’s choice for these papers was natural in the sense that

they are common paper, and consequently intrinsic to Chinese culture.

With these two extremes, black and white, she had an enormous palette

of variations to play with. She could then compose much more with the

effects rather than the representational forms of objects.

Lin Yan,

"Curtain #1", Xuan paper, 94" x 78", 2005,

© Lin Yan |

Lin

Yan, "Raining Inside II", Ink, resin and

Xuan paper, 75" x 67" 2006, © Lin Yan

|

In pieces like Curtain

#1 and Raining Inside II, we can find a historical richness of white and

black. And because of this tradition, there is

also a possibility for openness, for new superimpositions that the

artist has to confront the passing of her own days with time. She is

preserving her heritage in an essential way, not a representational

one. If physical details appear here and there, like rivets, they serve

as an invitation to memory. They are details whose significance has

already changed. In ancient China, important doors, such as the gates

of Beijing’s Forbidden City, were covered with golden doornails.

Detail

of rivets in Lin Yan painting.

© Michèle Vicat 2010 |

Rivets also belong

to industrial architecture. In her former studio in New York, Lin Yan

had a metal floor and brick walls. What appears

at a quick glance to be universal (brick walls and rivets for example)

can actually express different realities. The implications are different

depending on the context. “I find myself flowing between categories

or borders rather than resolving the tension between representational

and abstract forms or, by implication, tradition and change,” elaborates

Lin Yan in an interview given to Scott Ritter in 2006. (Lin Yan, Echoes

in the moment, catalogue published by China 2000 Fine Art).

Architecture, painting and sculpture have an impact on her work beyond

their own specificities. Lin Yan started to be interested in space

during her graduate studies in America. She also understood that she

could not abandon painting, more specifically the essence of painting.

She did not want to reproduce objects, flowers, and humans. She knew

she could do that, very well indeed. She realized that the focus was

no more the painting itself. Dynamic relationships coexist between

the painting, the wall and the space around. She then decided to use

a material that would bring her this flexibility: the xuan paper. She

needed to construct a new space in which no frame, no border would

delimit her vision. “When I have a solo show,” she told

us in her Brooklyn studio, “I will see the space first, and then

design each work individually, to shape it for that space. So, my work

evolves from a unique shape to accommodate a single wall to different

shapes to accommodate a space. I like sculpture and architecture and

I conceive my work within these orderliness. I start to think about

a space, and this is not in two-dimensional forms. There is a three-dimensional

element in my work.” The dilemma is how to integrate painting,

sculpture and architecture. How do you link them? Her instinct is to

re-think painting as something “simple.” Something that

goes to the core of her intimacy.

Lin Yan,

"Remaking", Xuan paper, ink and wax, 78" x 78" x 18", 2008, ©

Lin Yan |

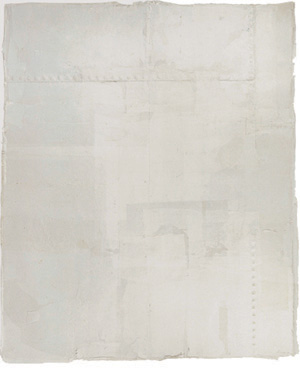

In Remaking,

done in 2008, she offers us an immaterial diffusion that brings us

to the frontier of universes where conflict and duality

echo the transaction the artist has to constantly re-evaluate in

order to bring her stories together. It is like the Yin and Yang:

making

things work together. Here the white finds a myriad of vocabularies.

It is rich, dense, theatrical, and textural. For centuries, Chinese

artists used paper as a flat surface. They did not bend it; they

did not compose with it. Lin Yan finds her freedom by reflecting

on traditional

culture and by proposing a radical transformation. “Tradition

could help me (to) get out of tradition, just as contemporary ideas

could help me get into tradition,” she explained to Scott Ritter

in the same article. The loop is closed and reconnects the infinity

of our aspirations.

Lin Yan uses

different moulds for her work. One that she took from an old brick

wall in Beijing is fiberglass. She also uses a plaster

or rubber mould taken from the metal floor of her former studio in

New York. She has recently started to use one made from tree bark.

Beijing and New York are revealed in a new interpretation that we

can find in the sculptural effect

that she gives to the paper. She paints her paper in different

shades of black with ink and water.

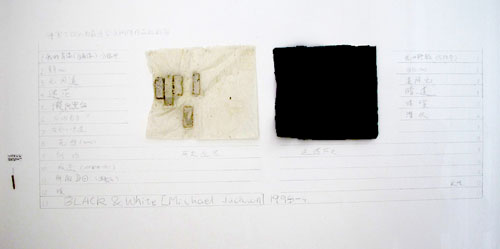

Detail of a mould |

She carefully arranges and mounts layer after layer of xuan paper

into her moulds. The layers are encrusted into the mould with the

help of a traditional brush made from the fibers of a palm tree

(zongshu.) The accumulation of sheets forms a flexible cast that

she will shape

in different arrangements. Her paper then takes a new strength,

an abstract transmutation. The whole process creates an imaginary

sculpture

that dialogues with something that is very flat to start with:

the process of a painting. Lin Yan pushes the envelope to find

a kind

of order within the complexity and duality of genres (painting/sculpture;

abstract/non-abstract) and of visions (Yin/Yang; East/West; feminity/masculinity.)

The duality does not involve rivalry, opposition or intransigence.

It is an inward notion that opens a path for us.

Lin Yan,

"Path", Ink on Xuan paper mounted on the wall, 96" x 80", 2002,

© Lin Yan |

| Path (2002)

lets us walk along an imaginary “Fil d’Ariane” (Ariadne’s

Thread), a path blazed in the silence of our individual existence

stripped bare. The gallery’s brick wall is covered with

many brick-sized inked papers imbedded in the artist’s

visual memory. Their echo is personal. The white patches, acting

as stepping-stones, lead us to the fluidity of our silent voice,

the voice that questions our cultural memory. They are like

sediment that delicately accumulates at the bottom of an ocean,

and whose mystery lightly touches us. It is the fusion of the

whole, the integration that opens the path to the deepest questions

about our past, our present and our future. But do not these

three dimensions in time form one? |

Lin Yan,

"Untitled", Ink, Xuan paper collage on wood with steel, 68" x

13" x 16", 2003, © Lin Yan

For more information about Lin Yan and to see more of her

work, visit her website

http://www.linyan.us |

|

All material

copyright 2010 by 3DotsWater |