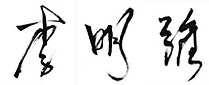

100 Days with Lily, courtesy of the artist and Lombard Freid

Projects, New York, 1995 |

100

Days with Lily is a very intimate and physical project that has

great personal meaning for the artist. It was

undertaken and carried on in the memory of his grandmother who

passed away in Taiwan while he was in California. She was the

first woman from Taiwan to study western medicine in Japan, and

she opened her own clinic when she returned home in the 1930s.

Lee Mingwei was deeply affected by her death and he felt that

he needed to spend some time with her, and the memory of her,

in order to accept death as a passage. He planted the bulb of

a lily, and he followed the steps of its growth, blossoming,

wilting and death. The artist lived with the plant and carried

it for 100 days. Each change in the state of the plant was carefully

noted on the day and hour that it took place. A photograph shows

Lee Mingwei’s hands holding a pot with the plant whose

flowers have just faded after the natural cycle was completed.

The image serves as part of a diary. We can follow the artist’s

daily involvement with the plant. Day 61 – 18 :32 Studying

with Lily. Day 75 – 09 :07 Walking with Lily. Day 79 – 11

:43 Death. But life continues in the heart and in the memory.

We have to let it go, but not necessarily at the exact moment

of disappearance.

Finally, the plant is exhumed on Day 100, because it is time

to let it go. The time limit may be artificial, but it is the

one that best promises continuity. « I carried the plant

24 hours a day for 100 days, » explains the artist. « Basically,

after 80 days, it was already dry, but I did not feel like letting

it go because it became a very important part of me. I prolonged

the for an extra 20 days. Then I exhumed the plant

and put it back in the earth. For Taiwanese, the water lily has

a very special identity. In its bulb form, it looks physically

like a male scrotum. So, it is a male organism, spiritually.

When it germinates, blooms and blossoms, it becomes a female

organism. And when it fades, it becomes a male organism again.

It was important for me to experience the phases of birth, growth,

deterioration and death over 100 days. It was a way for me to

mourn the passing days of my grandmother. »

At that time, Lee Mingwei was working as a weaver in a textile

factory in California. Every day, he would carry the plant with

him in the bus. People in the bus, mainly Hispanic, started to

talk with him, because he looked like a spiritual man with his

short hair and long robe. Older women started confessional conversations

with him. The project, although intimate in its conceptualization,

took on a public face with the spontaneous participation of people.

Time is central to the process of Lee Mingwei’s projects.

It is a variable, which can be expanded in the sphere of the

concrete or the sphere of the immaterial. People may respond

to his installations or they may not. He has learned to accept

this. This readiness to accept what is in the process of happening

comes from Lee Mingwei’s Asian background. Born and raised

in Taiwan, he comes from a family with a very long involvement

in medicine. His parents expected him to continue the tradition

of the eldest son. In college, he first studied biology for four

years. But his parents were concerned when he told them that

he fainted when he saw blood. They ask him what he wanted to

do. Lee Mingwei recounts in a very amusing way his conversation

with his parents: « When my parents asked me what I wanted

to do, I wanted to say ‘art’ but somehow I blurred

something like ‘artitecture’ and I ended in architecture

for 4 years. Wonderful subject, but, for me, it was a discipline

that does not allow any wrong steps. If you miscalculate, the

building collapses. Very rapidly, I realized that I want to practice

a discipline that does not have any right or any wrong. The subject

has to privilege the creation of ideas.»

Having lived in the United States since the age of 14, Lee Mingwei

feels completely bi-cultural. When we met in his New York apartment,

he was dressed in a traditional long silk robe of an exquisite

pale blue. The cloth moved gracefully around his slender figure.

In the entrance, nice flat embroidered slippers were waiting

for me. The place looked and sounded restfully calm, ordered,

inviting to a quiet conversation, although the view from the

windows showed the crowded and busy streets of the Wall Street

district. Lee Mingwei explained that when he is in a certain

environment, the uniqueness of the other culture works better

for him. His Asianess reveals itself in an American environment

and his occidentalness is more obvious when he is in Taiwan.

When the family left Taiwan, Lee Mingwei was 13. He stayed for

one year in the Dominican Republic in order to obtain a visa

to go to the United States. In his high school in San Francisco,

he studied ancient Greek and Latin as well as English and Spanish.

At that time, he hungered for classical Chinese literature. The

uniqueness of Chinese culture comes to him when he is away from

its geographical context. But, how does Lee Mingwei envision

his Chineseness? « When I am here (meaning in the United

States) I have a better understanding of where Taiwan is, where

China is in terms of historical context. I understand that I

am also culturally part Japanese, part Chinese, but nationally

Taiwanese. How do I blend these things in a harmonious state?

I see being Chinese as a cultural heritage but not as a national

identity. »

When Lee Mingwei went to the Chinese mainland for the first time,

he felt the scars of people and the destruction of the richness

of China’s traditional culture deeply. Taiwanese have remained

Confucians. The Cultural Revolution tried to destroy Confucianism.

.jpg)

The Dining Project at the Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, Japan.

Courtesy of the artist and Lombard Freid Projects, New

York, 1997-present |

When looking

at Lee Mingwei’s installations, one is filled

with wonder. The precision in the orchestration and the elegance

in the design echo his studies of biology and architecture, two

disciplines that require method. From the BA in Textile Arts

and the MFA in sculpture, he absorbed the sensibility for materials

and the projection of ideas and forms onto the public sphere.

Coming from the West Coast, the young man felt isolated when

he arrived at Yale University in 1995 for his graduate studies.

He elaborated the Dining Project, a one-on-one project

focusing on themes such as intimacy, trust, anonymity and self-awareness.

The project started as a projection of an old Taiwanese custom

in which newcomers in a village or in a small town go to the

soy milk breakfast place (doujian dian). Hospitality requires

that the newcomer be invited into homes and eventually to meet

the whole village. Based on the idea of « meeting the whole

village, » Lee Mingwei thought of doing something similar

in New Haven. He posted hundreds of posters around the campus

asking people interested in an introspective conversation and

food sharing to contact him. The first day, 45 people showed

interest! For a whole year, Lee Mingwei cooked three to four

nights a week. The « rules » were that the meal would

be prepared according to the individual’s dietary preference

and that the participant would be highly encouraged to converse

freely during the meal. The meal would be served to a single

person and there would not be any conversation during the dinner.

The acquaintance with the stranger was to be accomplished before

the actual meal.

The Dining Project operates at two levels. There is the elaboration

of a relationship with a complete stranger. Then the food acts

as a medium for mutual trust and intimacy. In 1998, the Whitney

Museum commissioned the show with a few variations. This was

the beginning of Lee Mingwei’s entry into the world of

museums and institutions. The Whitney Museum created a lottery

making the selection of participants unpredictable. The installation

per se was very simple: a tatami and a low table. The whole process

was recorded on video, with the camera lens at the level of the

food. The anonymity was preserved. The video was projected the

next day on the wall behind the tatami installation. Bits of

the conversation were audible. Pieces of the action of eating

and sharing food and conversation were visible. The project became

then part of a museum, a public space, where visitors could explore

change through interaction.

.jpg)

The Dining Project at the Whitney Museum of American Art,

New York.

Courtesy of the artist and Lomnbard Freid Projects, New

York, 1998 |

In 2006, Lee Mingwei embarked on a project with a larger

physical and emotional dimension. It was based on the

concept of impermanence.

Gernika in Sand, a mixed media-installation, was first conceived

at the Albion Gallery in London. The reference to Picasso’s

masterpiece is used here to meditate on the damage done to people

when they are victimized. Lee Mingwei’s partner miraculously

escaped death on September 11, 2001. More than 400 of his colleagues

died that day. In his work, Picasso depicts the massacre of Basque

civilians by the Spanish nationalist forces under Franco just

before the outbreak of World War II. Gernika in Sand (the name

of the place in the Basque language) expands the idea to all

victimized beings. « My first great experience of a western

piece of art, physically, was Guernica, in the late 1970s, when

it was still at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Picasso

wanted that piece returned to Spain only when the country would

have full democracy. I was so stunned by the sheer size…the

paintings I saw before were beautiful paintings from the Song

Dynasty with birds and flowers…but nothing like this

in black and white and grey with people screaming. It has a

political

message behind it. My parents were much involved in the Taiwanese

Independent Movement and, suddenly, I realized that the Picasso

had some aspects of it. »

Gernika in Sand at Queensland Gallery of Modern

Art, Brisbane, Australia.

Courtesy of the artist, Lombard Freid Projects and Yeh Ron

Jai Culture and Art Foundation, Taipei, Taiwan, 2006-present |

The choice

of sand as the primary material recalls the sand mandalas created

by Tibetan Buddhist monks. Mandalas are

reflective pieces

on the ephemeral nature of material life. Sand, a ‘powder’ created

from the erosion of rocks by wind and water, will again

become rock one day. When one thing changes, other things

can come from

it. Lee Mingwei used 40 tons of sand to create a 50-foot

long by 30-foot deep reproduction of Picasso’s painting.

But here, we go beyond the idea of a reproduction. Gernika

in Sand

took on its own life by becoming a performance articulated

around four phases.

The first phase was to have a nearly completed sand-version

before the exhibition opened. One small fragment of the

composition was missing because the artist wanted to show

that it was

a performance

in phases. The composition was left untouched for weeks

so people could come, see it and absorb it in this undisturbed

phase. On

the Monday of the 7th week, at sunrise, the artist completed

the piece using the whole day. It was the signal that people

could begin walking barefoot on the sand, one person at

a

time while he, the artist, simultaneously finished the

piece. The

alteration became a ceremony, which would be internalized

differently by each individual. It was a dynamic between

two people who

efface and create. An artificial island placed on the composition

allowed

visitors to take a step back, and to physically see and

emotionally live the process of destruction and creation.

At sunset,

the artist invited 3 visitors to brush the sand with him

toward

the middle of the disturbed composition. That would be

the stage

at which people would see Lee Mingwei’s work for the next

6 weeks. Only a small fragment of the original composition was

left untouched for people to identify Picasso’ s

artwork. Impermanence and destruction-creation effect purification.

What is important in Gernika in Sand is that perception

is

very different

from one person to another one. The artist himself experienced

changes throughout the whole process.

«

For me, the enlightening experience was to look at it at the

beginning, being involved in the creation of something beautiful

and then, at the end, to realize that it was completely destroyed.

Interestingly enough, a lady came almost every single day because

she realized it would be destroyed. She became very agitated

when the day became closer and closer. She was one of the last

people to walk on this piece before the sun set. Then she watched

me brushing up. She came to me and she was in tears. She said

to me that before that stage it was for her about death. She

said that at that stage the death mask had been lifted. Life

comes out. It took me a few seconds to realize that she understood

my work though me, the creator, did not understand it. » Beauty

comes from healing and is a way to respond to victimization.

.jpg)

Bodhi

Tree Project for Queensland Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane,

Australia. Courtesy of the artist and Queensland Gallery

of Modern Art, Brisbane, Australia, 2008-present. |

The Bodhi Tree Project (2008) is very close

to Lee Mingwei’s

heart. Maybe because the project involves physical, cultural

and emotional transplantations and assimilation. It is

like his life: a perfect harmony between past and present.

The project

was commissioned by the Queensland City Government of Brisbane,

Australia, for the inauguration of the Queensland Gallery

of Modern Art. The museum wanted a public art project.

Lee Mingwei

proposed going to Sri Lanka to bring back a branch of

the Sri Maha Bodhi, or the tree of enlightenment. Two thousand

five

hundred years ago, Siddhartha Gautama, the historical Buddha

and founder of Buddhism, is said to have sat under this

tree in Northern India. People wanted to cut down the tree

in a wave

of destruction that followed Buddha’s enlightenment. According

to the story, the night before the destruction, Princess Ashoka

(Sangamitta) took a branch from that tree, hid it in her hair

and escaped to Ceylon, which is today Sri Lanka. It took four

years for Lee Mingwei to convince the government, the high priest

and the village of Anuradhapura to give a branch of the sacred

tree to a non-religious institution. Lee Mingwei remembers every

detail of this adventure: « For me, it was to convince

them that, in the West, we go to museums as going to temples

for the art. We go there to be enlightened. A week before the

cutting of the branch, all the villagers were sitting under the

tree, chanting to the tree for the departure. I was extremely

nervous when the high priest handed me the branch. The priest

spoke to the tree in English! He said: ‘You are going to

a beautiful and exotic land. Your job is to be as tall and as

strong as you can so you can create shade for animals and people

there.’ » The branch had to stay in quarantine for

7 months because it is an exotic species. But, it was in good

hands by an accident of fate: the customs officer assigned to

the tree was from Sri Lanka! She thought it was karma and dharma

that gave her a chance to take care of this tree. The tree is

now 20 feet high and not only provides shade to visitors but

has become a meeting point for the Buddhist community of Australia.

It is extraordinary proof that public art can be a living and

sacred object. From an early age, Lee Mingwei grew up learning

the principles of Ch’an, a Chinese version of Zen. His

apprenticeship in classical Chinese literature and calligraphy

opened the doors to discover « the essence of Buddhism, » as

he says, « not the Indian part but the Chinese

part. It is about impermanence, about that philosophy

of nothingness,

about tastelessness like water. And that really affects

my work.

It is something visceral about being a human being. It

is about the mundane essence and the simplicity of being

a human

being. »

Bodhi

Tree Project for Queensland Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane,Australia.

Courtesy of the artist and Queensland Gallery of Modern Art,

Brisbane,

Australia, 2008-present. |

Reaching the innermost depths of oneself is the core

of Lee Mingwei’s

conceptual projects. He facilitates the exploration of our « I » by

placing us in a conversational environment with other human beings.

Situations do not have to be fixed in advance. They develop slowly

around a very simple action that forces us to reflect on the « we » that

we are establishing if we take the time and if we make the effort.

From the time Lee Mingwei graduated from Yale University, he

kept a very personal relationship with one gallery based in New

York’s Chelsea district. The Lombard-Freid Projects understands

the artist’s commitment to museums, institutions,

biennales and triennials around the world.

| The

Mending Project at Lombard Freid Projects, New York. Courtesy

of the artist and Rudy Tseng, 2009-present |

The Mending Project, 2009, is also based

on a simple idea that developed in the gallery as

a performance.

The installation

was minimalist: 450 bobbins of thread, neatly placed

on two panels,

a table, two chairs and a small sewing kit. People

were invited to come to the gallery and bring something

to

repair. The

conversation

started when people chose the color of the thread,

sat down and looked at the mending process. « I celebrate the rip, » says

Lee Mingwei. « I try not to hide it. Then, when it is repaired,

the thread is still attached to the garment. A pile is building

up and there are more threads pulling from the wall. It is like

a lot of my projects: it is cumulative. » The

process started when the show opened, not the other

way around

as usually happens

in a commercial gallery. The project here takes its

full social dimension as the conversation between

the artist

and the participant

takes place while the artist repairs the garment.

In the end, it is about the objective of work. How

do

we integrate

our

actions into our lives, how do we share this with

others. Ultimately, Lee Mingwei creates a place to

go, to develop

an intimate story,

which he then entrusts to us so we can explore it

and share it

with others. |